'Adolescence' and the power of story

Fictional characters can do something the rest of us can't

“The way to turn an ex-lover into a friend is to never stop loving them, to know that when one phase of a relationship ends it can turn into something else. It is to know that love is both a constant and a variable at the same time.”

I’ve been thinking about fiction and why you might read it when there is so much good and crucial non-fiction you could be devouring. Why pick up a novel when you could be reading what happens behind closed doors at Facebook? Why read about three daughters picking cherries in Michigan when you could be learning how whales are helping to fight climate change?

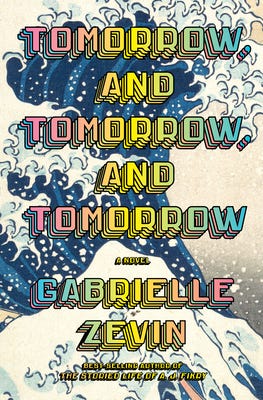

The conclusion I’ve come to is that there are insights you can get about the world that only come from fiction - or at least, can come most meaningfully and economically from fiction. The above quote is from the book next to my bed, “Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow” and it’s a lovely idea that I’d never come across before. Could I have learnt it from a non-fiction book? Maybe, but having spent a few hundred pages getting to know the characters involved I feel this lesson more deeply, and I believe it. It made me think about my own life and relationships, and then about the people I know who somehow manage to have long and fulfilling relationships with the people they used to sleep with. I didn’t need a self-help chapter called “How to stay friends with your ex” - I got to watch someone else do it then read, in fewer than 50 words, what their secret was.

Good novels are full of these moments - you might get 20 great life lessons on 20 different topics in a work of fiction, and because you feel as though you are in a fully constructed world when those lessons come to you, they stick much better than someone with a PhD telling you how you ought to behave. I’ve started taking photos of the page when I come across these moments in novels: the modern equivalent of underlining in pencil.

Here’s one I took from Tom Lake, where the narrator starts to realise that the boy she loves is sleeping with her friend and reminding her of Veronica, who the narrator betrayed in a similar way when she was young:

“In retrospect my inability to put it together was its own sort of gift. I would understand what they were doing soon enough, at which point I would finally understand what I had done to Veronica. Veronica had such a small part in the story and still I loved her more than everyone at Tom Lake put together. She stayed with me after the rest of them faded, maybe because we remember the people we have hurt so much more clearly than the people who hurt us.”

Poor Veronica. Poor narrator. Is that last line true? I don’t know, but upon reading it it’s almost impossible not to stop and think, again, about your own life and the choices you’ve made, the regrets you’re still holding onto. In the context of the book, you feel the narrator’s pain about Veronica because you’ve been living inside her head for so long. Again, having a non-fiction author tell you something is true doesn’t have nearly the same resonance as when you’ve experienced it alongside a character you care about.

**********

Which brings me to Adolescence, which has people at my stage of life (young kids, active Netflix-subscription, trying to find the right parenting path when all paths seem to be on fire) talking to each other like no other show in recent history.

Vic and I watched it over four nights, admiring the one-shot wizardry and mostly excellent acting. I don’t always know how much she’s enjoying a show but assumed she’d been as affected as everyone else by this one, but when I turned to her at the end of the season she was like, “meh”.

I tried explaining to her that because the entire Western world was talking about how good the show was, objectively she must have enjoyed it too. But she was unmoved.

“It was all right,” she said. “But it’s all stuff we knew anyway.”

She’s right about that. She and I have devoted most of our recent lives to researching, understanding and attempting to communicate the dangers of the online world. I must have done 30 long form radio interviews, each one more depressing than the last. On Monday I talked to a woman who demonstrated how social media use was destroying the ability of young people to take part in the democratic process, joining the list of things to watch out for including harmful content, sexual predators, reduced attention span, erosion of social skills, eye problems, intensified bullying and arrested emotional development.

Even people not as devoted to the topic as us already know a lot of this stuff. But I think the reason Adolescence resonated is because it was fiction. Imagine a documentary that told you about the manosphere, warned about the dangers of radicalisation and implored you to take more control over the time your child spent online. It might be convincing to the people who watched it, but it wouldn’t travel nearly as fast as far as Adolescence, a show which makes you care about the characters, which puts you in the shoes of the parents who wouldn’t or couldn’t monitor their child’s internet use and relied, like many of us, on a strategy of “hope for the best”.

I think among the show’s many achievements is its ability to “trick” people into learning about the harms of unsupervised internet use, in a way that (sadly for me) a radio interview with an expert never could.

Jonathan Haidt’s non-fiction book The Anxious Generation - one year old this week - has been a phenomenon too. But while it takes only a few hundred thousand copies to get such a book to the top of the bestseller list, tens of millions of people have watched Adolescence in less than a month. I don’t know whether the book or the TV show will have the biggest impact on societal behaviour, but you have to think that any parent who felt something in that last line of dialogue in Adolescence must be, in that moment, as close to changing their own online parenting choices as they’ll ever get.

Haven't watched the show (don't have adolescents & so much else to watch/read/experience in limited time 🤷) but totally agree with you about fiction having an "in" that often straight fact-based non-fiction doesn't. In some respects it gives the reader PERMISSION to see perspectives that otherwise they would avoid, but because it is part of a fictional story it allows them to rationalise giving them headspace, and possibly taking some of it on board in real life.

I read a series of fiction by a writer whose stories revolved around sucking you into being apalled by some characters, sympathetic to others, and then totally "flipping the script" later when you realise the crazy wife & the adoring husband were actually totally opposite, and the sympathetic third party observing it all ends up killing "the bad guy". Every book has a conundrum - was a murder justified because of 1) the extreme behaviour/abuse of the killed towards others? & /or 2) the saving of future victims of the killed? & /or basically self-defence as in prevention of the inevitable abuse? Although in other stories by the same author some of the murders, while of not-nice people, were for the convenience of the murderer (eg disposing of a blackmailer). It was interesting the change in perspectives & mindsets which can ONLY happen in fiction, although in this respect non-fiction/fictionalised re-enactments of "true crime" can approach this I guess? Certainly made me ponder whether SOMETIMES a murderer should be able to get away with it 😱

Great post, Jesse. Your comments about fiction vs non fiction sparked in my mind the old creative fiction adage: "show don't tell". It seems to me that non-fiction often struggles to "show" while fiction struggles to"tell".